Video Man Wathching Women Dressed as Sheep in Field

NPS/ Ann Schonlau

NPS/Jim Westfall

Bighorn Sheep are the symbol of Rocky Mountain National Park.

Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep (Ovis Canadensis)

Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep are the largest wild sheep in North America. Muscular males can weigh over 300 pounds and stand over three feet tall at the shoulder. Females are roughly half this size. Bighorn sheep are gray/brown to dark brown in color with white patches on their rump, muzzle and back of legs. Winter coats are thick, double-layered and may be lighter in color. Bighorn sheep shed these heavy coats in the summer.

They have wide-set eyes that provide a large angle of vision. This along with sharp hearing and a highly-developed sense of smell can detect dangers at great distances. Specialized hooves and rough soles provide a natural grip as bighorn sheep make precarious jumps and breath-taking climbs up and down sharp cliff faces.

As their name suggests, bighorn sheep have true horns that they retain throughout their life. Males, called rams, have large horns that curl around their faces by eight years of age. These horns can weigh up to 30 pounds. Females, called ewes, have smaller horns that curve slightly to a sharp point within the first four years of life.

NPS/Ann Schonlau

Life History

Bighorn sheep live in social groups but rams and ewes usually only meet to mate. Rams live in bachelor groups and ewes live in herds with younger lambs. Lambs are born in the spring and walk soon after birth. They nurse up to six months. Males leave their mother's group around two to four years of age, while the females stay with their herd for life.

Bighorn sheep feed on grasses in the summer and browse shrubs in the fall and winter. They seek minerals at natural salt licks like Sheep Lakes to add nutrients to their diet. Their digestive system acts as a survival mechanism. A complex, four-part stomach allows sheep to gain important nutrients from hard, dry forage. They eat large amounts of vegetation quickly and then retreat to cliffs or ledges. Here they can thoroughly rechew and digest their food away from possible predators. The lifespan of bighorn sheep is approximately 10 years.

NPS

Rams Actually Do Ram

Mating occurs in the fall when rams use their horns as weapons of battle to fight for dominance or female mating rights. In this display called "rut," rams face each other, rear up on hind legs and pitch forward at speeds up to 40 mph. The loud crash of horns signals contact and can be heard up to one mile away. This ritual is repeated until one animal concedes and walks away. Bighorn sheep skulls are thick and bony to absorb this repeated impact with little physical injury to the ram.

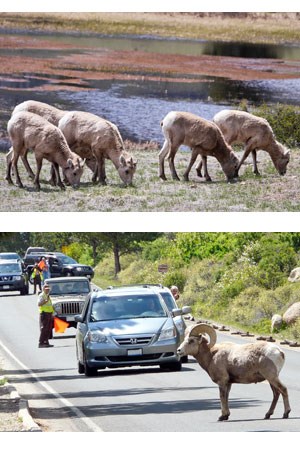

Bottom: Rangers help a bighorn ram cross the road.

NPS

Bighorn Watching

Bighorn sheep move to low elevations in late spring and early summer, when they descend from the Mummy Range to Sheep Lakes in Horseshoe Park. Here, they graze and eat soil to obtain minerals not found in their high mountain habitat. The minerals are essential in restoring nutrient levels depleted by the stresses of lambing and a poor quality winter diet.< /p>

Bighorn sheep visits to Sheep Lakes are hit-and-miss, but generally occur between 9:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. Groups between one and sixty sheep move from the ridge on the north side of the valley, across the road and stay up to two or three hours before reversing the trip back to the high country.

Studies show that crossing the highway creates high levels of stress in the animals, which can reduce their resistance to disease thereby increasing sheep mortality. In an attempt to protect the sheep, the park created a "Bighorn Crossing Zone" in Horseshoe Park. In late spring and throughout the summer, rangers control traffic as sheep move to and from the meadow. Researchers believe this has increased the intake of important minerals by the sheep, thus improving the health of the bighorn herd.

NPS

Trail Ridge Road provides the easiest access to witness sheep in their alpine range. They have been spotted between Forest Canyon Overlook and the Alpine Visitor Center.

Rocky Mountain National Park provides protection for all wildlife.

Because bighorn sheep are sensitive to human disturbance, please help in protecting the sheep by viewing from a distance.

-

Drive slowly and cautiously on Highway 34 along the north side of Horseshoe Park.

-

Do not enter the "Bighorn Crossing Zone by vehicle or on foot when sheep are present. Allow the sheep ample space to cross the road.

-

Stay by the roadsides when sheep are on the hill or in the meadow of Sheep Lakes.

-

Obey all signs and closures.

-

Do not attempt to approach sheep or make loud noises in their presence.

Bottom: Mid-twentieth century rangers monitor a sick ram at Endo Valley

NPS

Bighorn Sheep History in Rocky

The recent history of bighorn sheep in Rocky Mountain National Park is a dramatic story of near extinction and encouraging recovery. In the mid-1880's and early 1900's, the bighorn population declined rapidly. Initially, market hunters shot bighorn by the hundreds to receive high payment for then prized horns and meat. When ranchers moved into the mountain valleys, they altered important bighorn habitat and introduced domestic sheep. The domestic sheep carried scabies and pneumonia, which proved fatal to large numbers of bighorn sheep.

Under the pressure of disease, hunting and habitat alteration, the bighorn population declined until the middle of the 20th century. Research in the 1950's indicated that about 150 bighorn remained in the area of the national park. The surviving bighorn herds were in areas less accessible to human contact. Their range was limited to isolated, high country regions of the Mummy and Never Summer mountain ranges, and along the Continental Divide. The migrating, low-country herds were gone.

As the pressure of hunting and disease declined in the 1960's and 1970's, bighorn populations began rebounding. In an effort to stimulate population growth and promote diversity, wildlife managers reintroduced bighorn sheep to their historic ranges along Cow Creek and the North St. Vrain River in 1978 and 1980.

These new herds of bighorn along the eastern boundary of the park and the surviving native herds have continued to grow. Today, approximately 300-400 bighorn sheep live in the Rocky Mountain National Park area.

faithfulyeatcheed.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.nps.gov/romo/learn/nature/bighorn_sheep.htm